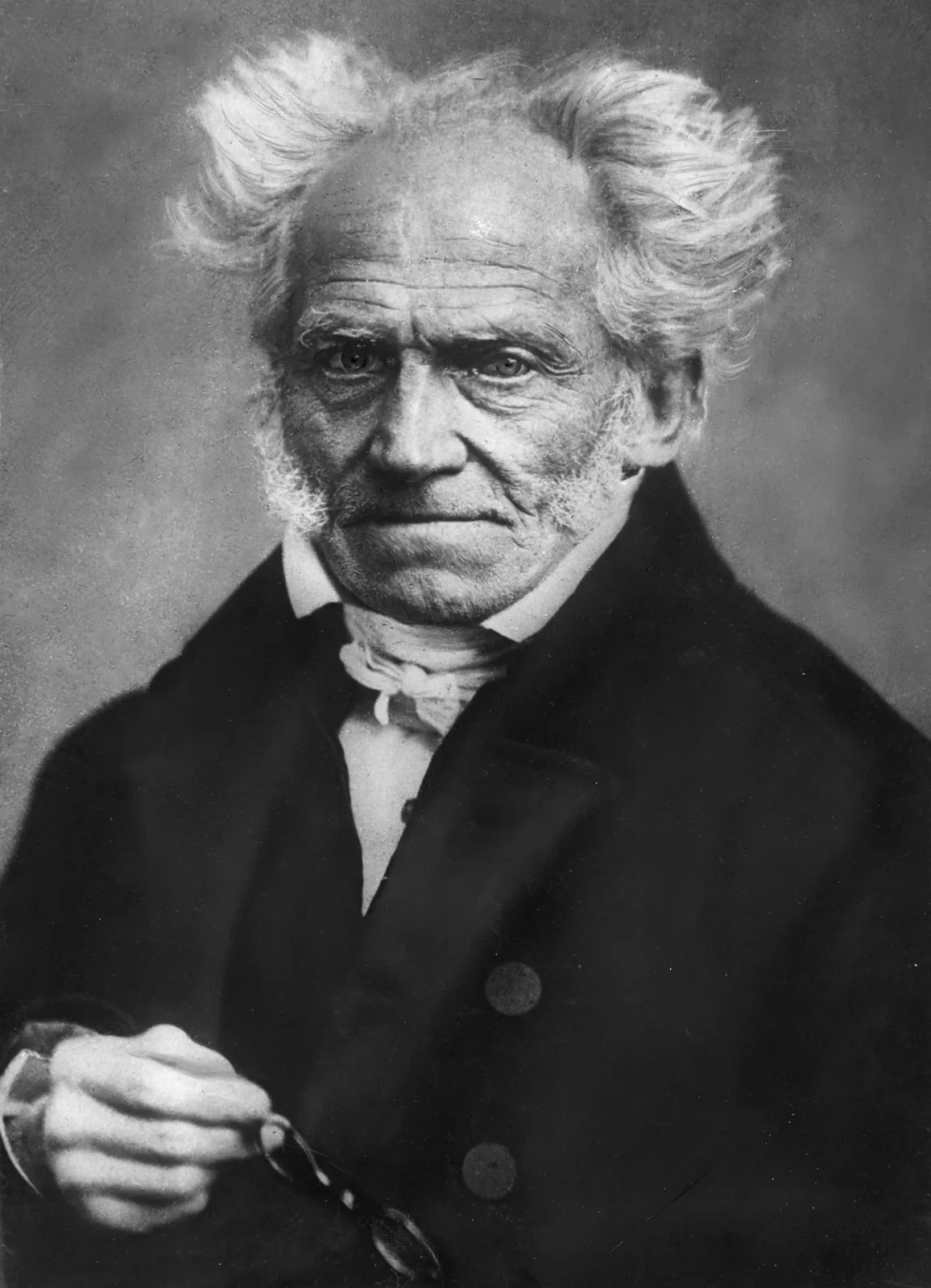

In the pantheon of Western philosophy, few thinkers have approached existence with such unflinching pessimism as Arthur Schopenhauer. Born in 1788 in what is now Gdańsk, Poland, Schopenhauer would become one of the most influential—yet initially overlooked—philosophers of the 19th century. His dark, comprehensive philosophical system would eventually shape the thinking of luminaries from Friedrich Nietzsche to Sigmund Freud, and his approach to aesthetics would earn him the title of “the artist’s philosopher.”

Early Life: Rejecting the Merchant’s Path

Born into wealth as the son of a successful international merchant, young Arthur was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps. However, his early exposure to the world’s suffering during family travels across Europe ignited an intellectual curiosity that would define his life. Rather than pursuing commerce, Schopenhauer felt compelled toward academics, driven by a desire to understand why the world seemed to function so negatively.

Against his family’s wishes, he attended the University of Göttingen in 1809, where philosophy captured his attention during his third semester. Though he later transferred to the University of Berlin for its distinguished philosophy program, Schopenhauer quickly grew disenchanted with academic philosophy, finding it unnecessarily obscure and detached from life’s genuine concerns.

The Overlooked Genius

By age 30, Schopenhauer had already completed the philosophical system that would eventually transform Western thinking. His dissertation “On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason” (1813) established the groundwork, while his masterpiece “The World as Will and Representation” (1819) presented his complete philosophical framework—a system from which he would never deviate throughout his life.

Despite the eventual significance of these works, they went largely unnoticed for decades. Throughout his 30s and 40s, Schopenhauer struggled as a lecturer and translator, finding little success or recognition. Only in his 50s did his work begin to attract attention, and true fame arrived only after publishing a collection of essays and aphorisms in 1851, just nine years before his death at age 72.

The World as Will and Representation

Building upon Kant’s transcendental idealism, Schopenhauer proposed that the world as we experience it is exclusively a representation created by our mind through our senses and cognition. We cannot access the true nature of external objects beyond our mental experience of them.

Where Schopenhauer departed from Kant was in his assertion that beyond our experience lies not a plurality of objects but rather a singular unified essence or force—what he termed the “Will to Live.” This unconscious, restless striving force toward survival, nourishment, and reproduction constitutes the core of all reality.

Reality, for Schopenhauer, has two aspects:

- The plurality of things as represented to consciousness (representation)

- The singular unified force of the Will

Importantly, this “Will” is not a conscious intention but rather a blind, purposeless striving that perpetuates itself simply for the sake of continuation. All material existence operates through this Will—moving, consuming, and violently expressing itself solely to sustain itself.

East Meets West

Schopenhauer stands as one of the first Western philosophers to systematically integrate Eastern and Western philosophical traditions. His conclusions about reality’s nature bear striking similarities to Hindu and Buddhist concepts, particularly in his assessment of reality’s negative relationship with the conscious self.

Like Buddhism, Schopenhauer’s philosophy is tinged with a profound pessimism: “Unless suffering is the direct and immediate object of life, our existence must entirely fail of its aim.”

The Philosophy of Pessimism

For Schopenhauer, the Will to Live is essentially malevolent, and we become its victims as it continues its mindless perpetuation. Since the Will has no aim beyond continuation, it can never be satisfied—and neither can we as its expressions.

We are driven to consume beings, things, and ideas, constantly hoping for satisfaction or happiness while being perpetually left unsatisfied after each achievement. As Schopenhauer bluntly put it: “Human life must be some kind of mistake.”

Finding Relief in a Suffering World

Despite his bleak outlook, Schopenhauer offered two primary methods for dealing with existence:

- Engaging in arts and philosophy: Good art provides clarity into the nature and problems of being without illusion, offering transcendent-like experiences that provide relief from existence. This concept made Schopenhauer one of the first thinkers to attribute philosophical significance to the arts.

- Practicing asceticism: By denying desires and self-indulgence, one might turn the Will against itself and overcome it. Recognizing the difficulty of this approach, Schopenhauer suggested that most people should focus on minimizing pain rather than pursuing ideals of happiness: “The safest way of not being very miserable is to not expect to be very happy.”

Legacy and Influence

Despite the limitations in his attempt to define reality beyond logic through systematic reasoning, Schopenhauer’s unflinching confrontation with existence’s harsh realities has left an indelible mark on Western thought. His work influenced:

- Artists like Richard Wagner and Gustav Mahler

- Writers including Marcel Proust, Leo Tolstoy, and Samuel Beckett

- Philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, and Ludwig Wittgenstein

As one of the first to philosophically question life’s value and the possibility of meaning, Schopenhauer addressed the emerging problem of a world increasingly detached from traditional sources of meaning. His fearless examination of existence—including all its horrors and miseries—opened new possibilities for finding answers from within.

For many, his dark, melancholic honesty offers a strange comfort. It reminds us that our sadness and suffering are not unfounded, but rather responses to a reality that can be hostile to our deepest yearnings. In acknowledging this truth, Schopenhauer provides a foundation for authentic living in a complex and often painful world.

This article is based on a philosophical exploration of Arthur Schopenhauer’s life and work. If you’re interested in learning more about Western philosophy or exploring other philosophical traditions, consider diving deeper into primary sources or comprehensive philosophical texts.